Some ten years ago, the Greater London Authority built Upper Banham underground station as part of a regeneration project in a once impoverished corner of north-east London. At first, it seemed a great success. Like wasps to a sandwich, young professionals swarmed into the area, house prices rose, and Upper Banham seemed destined for a prosperous future.

It did not turn out that way. Strange stories began to circulate even before the station opened. Workers stumbled across mysterious draughts as they dug the bluish London clay. Some complained of flashing lights or unaccountable mists; attacks of nausea and faintness were common. Some even claimed there had been disappearances, sometimes several hours in length. But these stories would have remained workers’ gossip were it not for a series of tragedies leading up to the disappearance and institutionalisation of a young commuter, Jonathan Mycock.

The first incident occurred just before nine o’clock on a busy Thursday in March. Well over a hundred people were crammed onto the narrow platform. As the northbound train approached, a shrieking figure tore onto the platform, bludgeoned his way through the crowds with the single-mindedness of a rugby forward stretching for the line, and threw himself onto the tracks. Reviewing the CCTV footage, investigators found that the man had started down the escalators to the platform some two hours before his frenzied appearance at the bottom. For those intervening hours, it was as though reality had forgotten he existed.

Neither the coroner nor the police investigation came to any definite conclusions. And it takes a lot to make commuters break their routines. But soon such a reputation surrounded Upper Banham that many began to prefer the longer walk to Manor House or the Number 29 to get them to town. A few weeks later, another commuter rushed, screaming, out of nowhere and into a group of late-night revellers. She remembered nothing and the authorities insisted she had been the victim of a fit, but after that only the brave, foolish or ignorant went near the place.

It would be flattering to call Jonathan Mycock brave and wrong to call him foolish; better to say that he was ignorant, despite (or perhaps because of) an expensive education at Canterbury and Oxford. His charm and intelligence ensured that he avoided the six months on the dole normally faced by a new graduate. Instead, one of the large consultancy firms offered him a traineeship and companies paid his employers huge sums for the benefit of his business experience (of which he had none).

Unfamiliar with the area and with London, Jonathan was not aware of Upper Banham’s sinister reputation. In fact, he was delighted to find that the tube ran so close to his flat. Had he a little more experience of the city he might have wondered why others crossed the street to avoid the place, or why he found himself alone on the platform in the heat of rush hour. Once, an older man on a bench called out to him to stay away, but Jonathan had already acquired the belief that no one speaks to a stranger in London unless they are up to no good and the warning went unheeded.

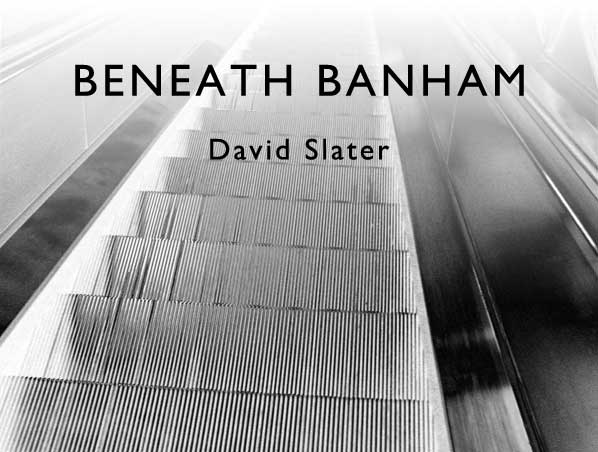

It was as quiet as ever when Jonathan entered the station bleary-eyed on a mid-summer Monday morning. It was his habit to skim the morning freesheet as he rode the escalator down to the platforms. Being a fast reader, and having no interest in celebrity or sport, he would usually finish the paper before he reached the bottom. On this occasion, however, an article attacking the failings of the Government caught his attention. When he finally exhausted the paper, he looked up and realised that he appeared to be not much nearer the bottom than when he had started. Strange, but perhaps the machinery was running slow today.

Now he noticed flashing lights, small pinpricks at the corners of his vision, growing into slabs of bright colour. He rubbed his eyes. The lights were brighter now. Gripping the rubber handrail, he told himself that it was the start of a migraine and wondered whether he still had painkillers at his desk.

The lights grew more numerous. Why had he not reached the bottom yet? He felt sick, and his head was beginning to hurt. He started to walk down but, as he did, it seemed the tunnel began to rotate around him. Disorientated and adrift, with the only fixed point the escalator tread beneath his feet, his balance deserted him, and he lunged for the side.

Crumpled against the handrail as the machinery drew him inexorably downwards, his arm aching, his head pounding, he saw thin trails of white vapour coming from the tunnel towards him. They swirled in the air, claw-like shapes that grasped at him as they passed, and each one that touched him brought with it a sense of extreme cold.

Suddenly there was something else; something like breath on his cheek. He cried out, his paralysis broken, and hurtled down the escalator, half-running, half-falling. Then he was at the bottom, the mist was gone, the light was gone, and all was dark, the only sounds the faint splash of water onto a hard surface and the rustling of what could only be rats.

Jonathan’s arm still hurt and his knee had twisted awkwardly where he had landed. His whole body was shaking like a tumble dryer. After several minutes, he finally found the courage and strength to get up from the floor and switch on the flashlight on his phone. By its wavering light he saw that the tiles on the wall were broken and covered in grime and mould. Those under his feet were cracked or missing. On a rusting sign the words “Upper Banham” were barely visible. Things scuttled in the shadows and something furry and warm brushed his leg. He leapt back, his scream echoing into the blackness.

Cowering against the wall, he saw seats and litter bins decayed or brown with rust. Rotting posters advertised strange new products and unknown films. Unwilling to face that escalator again, he slowly began to walk along the platform, staying close to the wall, flashing the light around him before taking each step. An emergency exit sign, its green arrow a faint symbol of hope, beckoned him onwards. Passing a peeling underground map, he saw unfamiliar lines with unheard-of stops. Still more disturbing were the omissions – a desolate white space where Westminster and parts of the West End should be.

Who knows how long it took Jonathan to reach the end of the platform and the emergency exit, but once he got there he found it secured with pitted and twisted metal sheets. The sight broke him. He called, then shouted, then screamed for help; his voice when I spoke to him days after the event was still hoarse and damaged. He pulled at the metal sheets, trying to wrest them from the doorframe, but soon ran out of breath and hope. He collapsed onto the floor and lay there, exhausted and terrified. What had happened to him? Where was he? Had anyone noticed he was missing? Was he going to expire slowly in a disused station that just an hour before had been the pride of the network? These thoughts went uselessly round his head like buzzing flies until, eventually, he found the resolve to stagger back along the platform. Much as he feared riding that escalator again, there seemed no other option.

Halfway along, he noticed a shrivelled newspaper on the remains of a plastic seat. As he picked it up, he heard a noise from the tunnel ahead; it sounded like jelly thrown onto a wet floor, slap, slap, slap. It was loud and getting louder. It was coming towards him.

In that moment, Jonathan made the decision that saved his life. Rather than run away from the noise, back down the platform to the cul-de-sac of the blocked emergency exit, he made a frantic dash for the escalator. As he did so, the chittering began. It seemed to come from everywhere at once, as though a thousand insects surrounded him. It grew louder and something brushed against his shoulder. It was a faint touch, but the pain ripped through his body and the wound would later need twenty stitches. As he floundered, the beam of his flashlight swung out into the darkness behind him and he glimpsed his pursuer.

What Jonathan Mycock saw drove any sense from his head. All he would speak of afterwards – perhaps all he could recall – was a single enormous eye, faceted like that of a fly and framed with stiff bristles. The eye alone, he said, looked like it could “swallow him whole”. The next thing he remembered was waking in the hospital bed. He could not remember reappearing in the modern station, or rushing headlong onto the platform, or the alert passenger who prevented him from flying headfirst into the path of an approaching train.

For the first three days after he woke, Jonathan said nothing. In time, he began to recover, though his nerves are weak and he will never go underground again. Upper Banham closed the day after the incident. The authorities, so long in denial, could not dismiss three incidents so similar and so close together. Government officials crawled over the place, but found nothing conclusive. Such a large investment could not be left closed forever and, in time, the station re-opened.

I spoke to Jonathan Mycock on three occasions. I spoke to the passenger who saved his life. I spoke to his doctors and to the police. And, having heard their stories, I say the Government should close the station and bury it in concrete or destroy it with explosives. I say this because nothing I heard can explain what Jonathan Mycock’s saviour took from his hand and showed me with a haunted look and a whisper, the thing that he has otherwise kept secret because he fears ridicule or worse: the shrivelled newspaper with the impossible date.