I hadn’t been looking forward to it.

“I’m going speed dating… in Surrrrr-bi-ton,” I sneered into many an ear prior to the event, laying out insult and injury in turn.

Then I TFL’ed Surbiton. It was even further south than Clapham, and might not even be in London.

“Whaaa?” I moaned, already totting up how much it was going to cost on my pay-per-go. I was already fifteen quid down from having signed myself up to “Date in a Dash” in the first place. Could things get any worse?

“Oh well, in for a penny, in for a pound,” I sighed, scuttling off into the bathroom to squidge dye on my roots, “you can’t make an omelette without cracking eggs.”

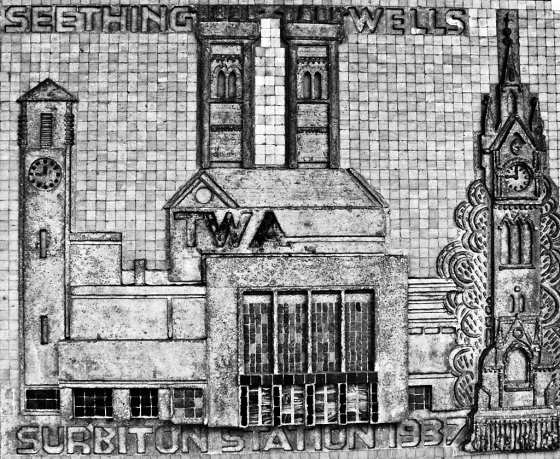

To be fair, the town’s founding fathers should’ve given the place a less synthetic name. As the ancient Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan is represented by a prickly pear on which a snake-wrestling eagle perches majestic, so Surbiton’s glyph, going by title alone, should be a bowl of towny soup going cold, with Waterloo choo-choos and Pooterish commuters drowning in the gloop. But it just goes to show: don’t judge an area formerly within the County of Surrey by its moniker. And, stepping off the South West cattle cart stuffed with workers in various stages of mental undo, my Oyster in the red because the agent at Finsbury Park had grossly underestimated how much it would take to get to Zone Six, I got the sick sensation of maybe having to eat my preconceived notions. It was the blackest of nights, as if designed to set off the dazzlingly white, art deco station, with its elegant rectangles and romantic sans-serif fontage, to best advantage. I could be in San Diego, Palm Springs! Closing my eyes, I sensed cocos nucifera, hummingbird and murdered starlet on the breeze; until an ear-cracking wind slammed into me, knocking the fantasy out cold (I hadn’t worn a hat, lest I get hat-hair for the date(s)).

I waved to my friend Rhi, who was standing across the car park, shivering. Even though she had a job, she had spent the whole winter hypothermic, on account of being an optimist.

“No point buying a thicker coat now, winter’ll soon be over,” she’d said. That was back in January. As I write this, the sky outside my window is sloughing its first spring snow. Haven’t heard from her in a while…

The pub was a mini Orkney, not a lady in sight, only rugged men with frost-nibbled beards hugging pints and staring at us as if we were quarry shipped in from the Far East to replace local female stock escaped to parts less chilly and depressing, like Kingston. I ordered two rum and cokes (normal, not spiced – we’re not complete Jezebels), and asked myself the question every speed dater sporting two X chromosomes must: why were we bothering to pay fifteen smackers to meet men when there were so many free ones lying about?

Taking our drinks, we found ourselves a table. Rhi had been out the night before, and could barely stop her eyes from shutting; if I still smoked, I would’ve propped them open with matchsticks. Before long, we were joined by Janet, our third stooge, who wafted in out of the cold looking like she might be naked under her snow coat. She’d died her hair Bratislava Red but, despite her make-up, looked wan. She’d been crying all day, she said, and we didn’t need to ask why: her younger sister had just had a baby, and was now living in Janet’s house in Mitcham along with a husband who never let her touch the new arrival.

It’s just until they get their new house fixed up. A year, two years, max…

I myself wasn’t bringing my A-game to the night. My nanna had died the day before, but I figured she would’ve wanted me to find love, even if I didn’t. Fresh-torn from an eight-year relationship, I was still an open wound under my sticking-plaster smile. On my way to the station I’d had to press my tongue firmly to the top of my mouth, and tip my head back, in an effort to staunch the flow of tears provoked by the memory of my dear-departed love, and by the thought of what I was about to subject myself to. Unlike Nanna, my love wasn’t dead – though I did consider telling people he’d perished in Hurricane Sandy after he dumped me over Skype with that force of nature tip-tapping at his Brooklyn windows as he did the dirty deed.

“So you’re depressed, you’re hung over, and you’re grieving. You’re basically The Undateables.”

That from Adelle, who wasn’t coming with us. She had two kittens, and a fiancée she’d met on the internet. They were getting married in August, in Tuscany, and already lived in Surbiton.

“August? Tuscany? Your dress is going to be boil-in-the-bag,” I whispered to Rhi, bridesmaid-in-chief. Rhi nodded, eyes closed, placing her chin on the table like a dejected spaniel. It was going to be a long night.

Ding!

My first date was a Kenyan called Nigel who did something with chemicals. Since booking, I’d been agonizing over what my tactic would be for the dates, what role I would play – because, of course, I couldn’t be myself: there was just too much to hide. But, under pressure, I found myself employing an unforeseen tactic: taking charge and firing queries at the dates in quick succession so they couldn’t get a question in edgeways.

Nige was nice enough, but when the GlaxoSmithKline building in Brentford is the main topic of conversation, you know it’s not a goer.

Ding!

Next was a Simon, who I can remember nothing about at all, except that he was called Simon.

Ding!

They came, one by one, like lambs to the slaughter, leaving my table six minutes later shot through with deflections, off to meet Rhi who I hoped would knock them dead with her cheeky Welsh charm.

Ding! Ding!

Daniel said he had a close-knit family that lived nearby:

“Are you Jewish?” I said.

“No,” he said, taken aback. “Why, do I look Jewish?”

I back-pedalled, mentioning the name and the close-knit family, even though I knew no insult had been levied. I was almost going to add that I had a penchant for Jewish men, despite having sworn no more after Zev and the whole “I left my heart in San Francisco” debacle (on the corner of Oak and Schrader, to be precise – I am the only Englishwoman who can boast of having her heart broken on both the East and West Coasts of the US), but I threw down my spade in time.

My “gaff”, however, provided a handy opener for all subsequent dates, saving me from having to dip into the ice-breakers provided on the bottom of our scorecards (What is your biggest pet peeve? Are you an early bird or a night owl? Thai bride or Russian?).

“Hi. Did you know I just accused the last guy of being Jewish?”

All the men seemed to live in Southey places I’d never heard of with “Thames” in the title. For that reason alone it would never work; my Oyster was already in the red, and I’m a dyed-in-the-jeggings Northerner. Guy, now sitting opposite me, was no exception. He looked like the late, great John Candy; so imagine my surprise when he told me he ran marathons. He also said he wrote comedy scripts, so perhaps he was pulling my leg.

Ding!

It seemed they’d saved the best for last.

Jim had a great nose, and told me he’d spent Christmas alone, in Whitby. I drifted off as he talked, and imagined Jim walking down a solitary beach, collar upturned, looking soulfully out to sea. We discussed what fish the town was famous for, and the communist it had once harboured.

“I work for a university, but I’m not a screaming left winger… just moderately,” he confessed with a shy smile in the last thirty seconds.

My pen hovered to tick Jim as a “yes”; only something stopped me, mid-scratch. Jim had a great nose, and liked Hilary Mantel, yes; but there was something wrong, something terribly wrong…

I excused myself at the final ding, and escaped downstairs for a wee. As I washed my hands the toilet door behind me flew open and Janet appeared in my mirror. Her spirits had somewhat improved, her hair all static, like it’d been rubbed by a naughty balloon.

“God, how many have you had?”

“Only two.”

We touched up our lipstick, and discussed our dates. I told her what I’d said to Daniel.

“Is that because you wanted to find out if he was a roundhead?”

I’d hoped to slink off, but when we got upstairs again I saw Rhi had got a round in, and was huddled with Jim and some of the others around my old table. Janet and I squeezed in, and we all chatted uncomfortably for a while, before salvation descended in the form of a rogue Afghani.

“Can I have a speed date! Please, give me a speed date!” he pleaded to each of us in turn. Then, sniffing out the weak link, he pulled Janet up by the hand and, before his six minutes were up, had our girl in a groin-grinding slow dance during which he whispered sweet, nonsensical nothings into her ear through a pile of hair static.

Jim and the others could only look on. I couldn’t tell if they were jealous, disapproving, or both; but it didn’t matter, really: it was too late for ticks to be rescinded – our scorecards had been handed in, all bets were off.

Ding!

I managed to persuade Rhi out of another drink and, prizing Janet from the Afghani’s arms, we waved goodbye to our dates. As we made our way to the door I noticed, sitting at a table in the corner, an empty space, shaped like a man; and I realized he’d been there all along, that ghost.

So I tipped back my head, and pressed my tongue to the roof of my mouth, and braced myself for the night.

Next day came the results. Janet told us she had sicked up her dinner when she’d got home, but had two potential lays. Rhi was depressed because no one had ticked her – no one she wanted, anyway.

“Daniel has, but, I dunno, I remember his eyes and teeth were all over the shop,” she said.

Janet was unimpressed.

“Don’t be so picky, Rhi. He’s got a lovely place in East Ditton, right next to Adelle and Pete.”

I agreed with Rhi: could do better. I myself had got no ticks, mainly because I hadn’t given any. You have to give in order to receive, in the speed dating game.

“It’s okay, because what I’ve realized is that I’m just not emotionally available right now,” I said, in my best mock-Californian.

No. I didn’t have to worry about it. Not any of it. Not speed dating, not Surbiton, not men with faces like smashed crabs or the fish that Whitby is famous for. I didn’t have to worry that I was thirty-three and had more personality disorders that you could shake a knackered Oyster at. Because I wasn’t emotionally available.

And, by some sick and twisted logic, that meant I could feel darn good about myself.