It was the summer of 1976 when we set fire to David McIntyre. Round the back of Brockwell Lido, bushes hiding us from the expanse of the park. Every now and then it comes back to me.

Take yesterday. Pete was on the sofa and I was in the recliner, tilted back a little. There was a ball of paper on the floor where the fireplace used to be, like someone had still expected it to be there and chucked it on as fuel. Pete had a half-empty wine glass of lemonade – he doesn’t drink in the week, and says the wine glass makes him feel it less. When I got up to get the paper I noticed some of the plaster over the bottom of the fireplace had started to peel. You think everything’s sorted and dealt with and you can have a rest, and then you have to start on something else, something you thought you’d finished with ages ago.

I had been talking to Pete about holidays.

“Do you know, babe, we’ve been everywhere: Madrid, Paris, Cologne, Prague, Oslo.” He looked up from his faux alcohol. “I quite fancy Finland next – Helsinki, probably, because I’ve heard of that.”

Pete didn’t look keen.

“It’s too dark and they drink too much. It would be weird,” he said.

“It wouldn’t be weird, babe, it would be like Peckham.”

“What about Spain again?”

It was so hot in Madrid. I couldn’t handle it. I got burnt and a bit tetchy. I had to keep lying down – I couldn’t stand upright at all. Kept taking my T-shirt off but it was so unbearable that I had to cover up.

It had been like that in ’76. Even at night it hadn’t let up. All over our estate was the same, kids out till all hours, trying to get some air, but there wasn’t any. Me, Kate Dawson, Geoff Wallis, Paul Fincher, out roaming the park. Kate, Geoff, Fincher – I haven’t seen them for years. After we set fire to David McIntyre it wasn’t the same. I started hanging out with a different crowd. I did different things with this new gang. Took my mind off it. One of the new lot, his parents had this massive paddling pool and a hosepipe, so we used to fill it up and spray each other down. I used to lie in that pool, face down, for as long as I could, just letting it all wash over me.

And I kept out of David McIntyre’s way. It was pretty easy, seeing as how he wasn’t going anywhere, even after he came out of hospital. Keeping out of his family’s way was harder, but they didn’t know about me: he’d kept his mouth covered.

A couple of months afterwards they had a benefit at the Prince Regent, and the rumour was that when they sent the bucket round for donations, someone put a box of matches in. My dad almost died laughing when he told me that. I remember him looking at me until I laughed too; nearly died of laughter.

I can’t remember why we chose David McIntyre. Because he was hot and bored like us? Because he also had parents who didn’t seem bothered that he was out so late? Because he lived in one of the bigger houses in a road named after a poet, before they got turned into flats and bed-sits?

“Wanna go round the back with me?” I’d asked him. It’s not like it wasn’t plausible. He was OK-looking, really. I was wearing my Marc Bolan vest top, and I knew he’d always liked me in that.

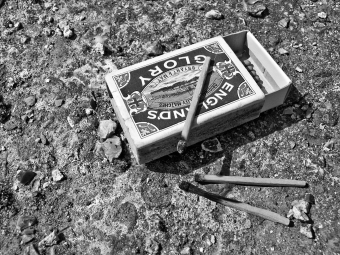

“What’s going on?” He’d clocked the others moving in, the gleams in their eyes, the hardness of their lips, the petrol can I’d got Fincher to bring from his dad’s garage. At the time I hadn’t known what for, but then I saw David McIntyre and I did. I wasn’t involved in holding him down; I just helped pour the petrol. As I splattered his shoes I saw that he was wearing his school plimsolls and they were white like mine. We all lit matches.

I don’t remember any screaming: it was as though the air was so thick with heat that night that any noise that came from his mouth just died on his lips; as though there just wasn’t enough air to transport his screams across the park. We were lucky; I said so.

I remember the laughter, though: those hard, silent laughs where your jaw locks open like a vice and your nose shrinks into your face and your eyes disappear. You can’t see. It makes you dizzy, like you can’t stand up straight. Oh, we were lucky.

I’m wondering if the luck will run out. Pete’s back soon. He’ll want his usual postwork wine glass of lemonade. He’ll wish it was sauvignon blanc. He’ll wish he was married to someone else. I wonder what would make him leave: what I did, or the fact that I kept it from him for all these years? I imagine making it easy for him, saying the words to him. I wonder what words I would actually use. Petrol. Matches. Laughing. Long hot summer. Long time ago.

So, Helsinki, maybe. The colder the better, really, although not ski-ing. I couldn’t stand all those log cabins, and the real fires.

When we bought our new house, when my business had taken off and we could go posh in Dulwich, it had all original features – chimneys, fireplaces, the lot. I had them all bricked up. The one in the living room, when they were doing that, about halfway through, a ton of soot fell out. One of the builders said it started trickling and, before they knew it, it just came down; must have been up there for ages, waiting for the opportunity.

So, now, all the fireplaces are bricked up and plastered over, and painted, or even – in the case of the one in what they call the master bedroom – wallpapered. But it doesn’t matter what we do to them; you can still tell what used to be there.